The Oxford English Dictionary defines apotheosis as “[t]he action of ranking, or fact of being ranked, among the gods; transformation into a god, deification”; it can also more loosely mean “[a]scension to glory, departure or release from earthly life.” There are several noted examples of apotheosis recorded in the annals of the ancient world. In Greek myth, there are the stories of Ganymede (the beautiful son of Troy, kidnapped by Zeus to serve as cup-bearer to the Olympians) and Psyche (the mortal princess who endured several trials of the goddess Aphrodite to achieve apotheosis and marry Cupid). In the biblical tradition there is the story of Enoch, the great-grandfather of Noah, who, it is said, “walked with God: and he was no more; for God took him” (Gen 5:22-29). Arguably the most famous apotheoses in the history of literature are to be found toward the close of Ovid’s Metamorphoses: for instance, that of Julius Caesar whom Ovid transforms into a constellation of stars.

English: Deification of Julius Caesar. Engraving by Virgil Solis for Ovid’s Metamorphoses Book XV, 745-850. Français : La déification de Jules César. Gravure de Virgil Solis pour les Métamorphoses d’Ovide, livre XV: 745-850. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

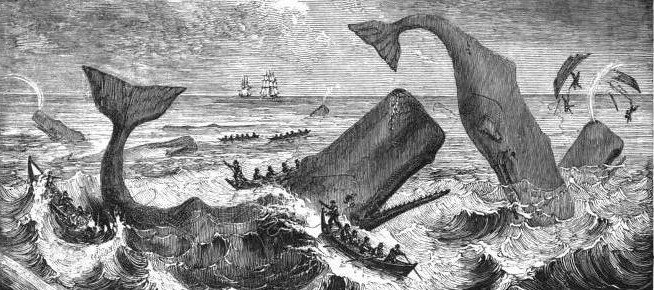

The apotheosis of the sailor Bulkington at the close of Chapter 23 of Moby-Dick, “The Lee Shore,” is a relatively uncommon example of this trope in modern literature. “Bear thee grimly, demigod! Up from the spray of thy ocean-perishing—straight up leaps thy apotheosis!” Several features distinguish the apotheosis of Bulkington from his ancient predecessors, not least of which is the fact that he is no renowned beauty or king among men but rather just an average sailor, though perhaps an unnaturally eager one: a man, it is noted at the start of Chapter 23, “who in midwinter just landed from a four years’ dangerous voyage, could so unrestingly push off again for still another tempestuous term. The land seemed scorching to his feet.” Indeed land does not seem to be Bulkington’s element but water, the very medium of his perishing and eternal life. Yet, along with the more democratic spirit infusing the apotheosis of this common man-before-the-mast, there is revealed an anxiety that the man might not in his essence necessarily follow the investiture of his glorious ascension. Ishmael, to paraphrase his exhortation to the “demigod” Bulkington at the close of Chapter 23, is urging that the man indeed be transported upward in the spray in which he will regardless forever read the endurance of his spirit.