Etymology—The Quarter-Deck—Sunset—Does the Whale Diminish?—Ahab’s Leg—Epilogue

Sunset—Dusk—First Night-Watch—Forecastle—Midnight—Moby Dick—The Whiteness of the Whale—Hark!—The Chart—The Affidavit—Surmises—The Mat-Maker—The First Lowering—The Hyena—Ahab’s Boat and Crew: Fedallah—The Spirit-Spout—The Pequod meets the Albatross—The Gam—The Town-Ho’s Story—The Ship—Monstrous Pictures of Whales—Less Erroneous Pictures of Whales—Of Whales in Paint, in Teeth, &c.—Brit—Squid—The Line—Stubb Kills a Whale—The Dart—The Crotch—Stubb’s Supper—The Whale as a Dish—The Shark Massacre—Cutting In—The Blanket—The Funeral—The Sphinx—The Pequod meets the Jeroboam: Her Story—The Monkey-rope—Stubb and Flask Kill a Right Whale—The Sperm Whale’s Head—The Right Whale’s Head—The Battering Ram—The Great Heidelburgh Tun—Cistern and Buckets—The Prairie—The Nut—The Pequod meets the Virgin—The Honor and Glory of Whaling—Jonah Historically Regarded—Pitchpoling—The Fountain—The Tail—The Grand Armada—Schools & Schoolmasters—Fast Fish and Loose Fish—Heads or Tails—The Pequod meets the Rose-bud—Ambergris—The Castaway—A Squeeze of the Hand—The Cassock—The Try-Works—The Lamp—Stowing Down & Clearing Up—The Doubloon—The Pequod meets the Samuel Enderby of London—The Decanter—A Bower in the Arsacides—The Measurement of the Whale’s Skeleton—The Fossil Whale—Does the Whale Diminish?

Sunset

Ahab sits in his cabin pondering, peering out his window—thinking meticulously to himself—reflecting on the conversations between him and his shipmates beforehand—he reflects how Starbuck calls him out for seeking revenge on Moby Dick—no matter what his shipmates say he will continue the to hunt Moby Dick—“The path to my fixed purpose is laid with iron rails, whereon my soul is grooved to run.”

top

Dusk

Starbuck is leaning against the mainmast—discusses how his sanity is controlled by a “mad man” (aka Ahab)—He is debating on whether or not to concede Ahab’s mission to hunt Moby Dick—but he doesn’t have much of a choice—the white whale has the whole ocean to swim, but Ahab is drawn to that challenge—finishes with a prayer: hopes “the soft feeling of human in [him]” will keep the “grim, phantom futures” at bay.

top

First Night-Watch

Stubb is laughing off the conversation between Ahab and Starbuck—he addresses life with a carefree attitude—he sings a little rhyming tune—Starbuck calls for Stubb—Stubb leaves off his thoughts to obey orders.

top

Midnight, Forecastle

*Insert harpooneers and sailors singing together and having conversations during the watch*— sailors encourage Pip and other sailors to dance and make music—they want women to be there to dance with—Pip plays tambourine while sailors dance all about the ship—Tashtego, while smoking, makes fun of the white men for actually thinking what they are doing is fun—he’s glad he didn’t break a sweat for it—Old Manx sailor wonders why it is that the young sailors are dancing—they should be young; he was young once—some more discussion about naked dancing women—poor lonely men—“sky darkens—the wind rises”—they start adjusting to the wind and the waves of the sea— sailors talk about how they have to take orders from Ahab because they are the ones who bring him the whales—they gang up against Daggoo for the blackness of his skin and whiteness of his teeth—man from quarter-deck shouts orders—“ALL: ‘The squall! the squall! jump, my jollies!’ [They scatter]”—Pip watches what is unfolding before him and narrates the scene.

top

Moby Dick

Finally we get a better glimpse at Moby Dick!—Ishmael is on the bandwagon in the quest for revenge against the loathed white whale—a history of Moby Dick is given—the reader learns that Moby Dick is infamous and has taken down a lot of ships—the question is raised as to whether or not Moby Dick has supernatural capabilities—most importantly, we learn the story of Ahab and Moby Dick—how he lost his leg to the “sickle shaped jaw” of the white whale—Ahab started going insane on his way home and his crew had to restrain him—#monomania—Ahab learns to hide his rage and madness, but he is nonetheless insane—Is it divine intervention that Ahab was maimed by this “vampire of the sea,” since he is now consumed and dedicated to the hunt?

top

The Whiteness of the Whale

Whiteness of the whale appalls Ishmael—he starts this rant by discussing things that people find beautiful that are white—pearls, stones, flowers, elephant tusks, etc.—and then discusses how whiteness is acutely fear-inducing—even when its good it’s evil—Ishmael cites several examples—the polar bear and his “ghostly, eerie whiteness—Albino people are sometimes stigmatized and feared—Ishmael concludes that it is albinos’ whiteness that makes people not accept them—according to Ishmael, the whiteness makes them “more strangely hideous than the ugliest abortion”—Melville makes another biblical allusion, this time to Revelations, where the devil rides a pale horse.

top

Hark!

A break from the ramblings of Ishmael—the scene is set on the quarter-deck; Cabaco and Archy are on middle watch and filling the scuttlebutt with fresh water—they have to be quiet as to not disturb the Captain—Archy hears something in the stillness of the night—“Hist! Did you hear that noise, Cabaco?”—Archy is convinced that he can hear something or maybe even a group of people underneath them in the hatches—he tries to convince Cabaco that it sound like there is people turning over in their beds—Cabaco dismisses the idea but Archy stand firm and suspects that Ahab knows what or who is down there—Remember what Elijah said about the figures? Remember Ishmael seeing them too?—Perhaps there is something here…

top

The Chart

Ahab spreads old, yellowed charts before him and studies them trying to figure out where Moby Dick will show up next—Ahab tracks the movement of currents because the whale’s food will travel along them—this way he can have a better understanding of the course the whales will take—#monomania—Ahab faced Moby Dick near the Equator, where the white whale seems to be every year at the peak of the whaling season—Ahab is growing impatient and trying to identify the path of Moby Dick based on stories of past Moby Dick sightings—he thinks that if he reviews the charts enough he will be able to intercept his nemesis—#obsession.

top

The Affidavit

Ishmael stresses the importance of this chapter, which is one of many wordy discourses on the subject of whaling—not many whales have ever been once wounded, escaped, only to be later killed by the same hand—whales gain prestige by wrecking ships—most sailors seek to avoid “more intimate acquaintance” (not so with Ahab!)—Ishmael makes sure to describe to us landlubbers how dangerous whaling actually is—only one in fifty whaling disasters are ever reported—Sperm whales can and do destroy ships—not whaling boats, ships—account of the Essex: ill-fated ship who butted heads with a sperm whale—the Essex lost that battle—Essex reduced to splinters, sank in ten minutes—Chief mate, Chase, swears that the whale meant to attack them—describes the event as “mysterious”—mysterious indeed, that the leviathan should turn upon its hunters—more descriptions and first-hand accounts of the whale’s strength and willingness to ruin your day if he so chooses—Ishmael guesses that the ship-destroying “sea monster” of the Sea of Marmora had to be a sperm whale.

top

Surmises

Ahab’s mind is laid bare—driven by a single purpose: #monomania—yet Ishmael hypothesizes that for every sperm whale Ahab slays, he feels closer to the White Whale—however, more psychology is at work here—men are the most finicky tools in Ahab’s repertoire—he must keep them in check—Ahab directs his “magnet” at Starbuck’s brain, forcing him to comply by sheer force of personality—but Ahab cannot use personality alone to fulfill his purpose—the crew is on the voyage to hunt whales, and he must oblige them—men must have “food” for the common urges—dreams and high causes mean nothing to men who are hungry—for all these reasons, Ahab lowers for whales other than the White Whale.

top

The Mat-Maker

Ishmael and Queequeg weave a mat for the whaleboat—the Pequod is still and silent, no whales yet—Ishmael’s mind wanders; he compares mat-weaving to the Loom of Time, simulating the interactions of free will and chance—an Indian war whoop!—Tashtego spots whale spouts—frantic activity aboard the Pequod—the sailors prepare to chase their prey—“phantoms” appear by Ahab’s side.

top

The First Lowering

Ishmael sees Fedallah for the first time—a devilish creature with a protruding tooth and a white turban of hair—Ahab is surrounded by Fedallah and other “aboriginal natives of the Manillas” —Ishmael gives a racist commentary on the reputation of these Filipinos—Ahab ignores the shock of his crew and clambers into his whaleboat—the crew shrugs off their disbelief and lowers after the whales—Archy confirms Ahab’s new crew belongs to the voices he heard in the hold—the whaleboat “knights” urge their men to row—Stubb is joyfully profane in his urgings—Starbuck whispers to his men in urgent but soft tones—the chase continues—Flask mounts Daggoo’s shoulders and urges his oarsmen loudly and stamps upon his hat—Ahab’s urgings are so profane Ishmael cannot bear to set them down—Ishmael is caught up in the excitement of the hunt—a squall approaches—Queequeg tries to harpoon a whale—the harpoon grazes the whale, and Starbuck’s boat is overturned—Starbuck’s crew get back in the boat and are caught in the squall—Queequeg holds up a candle by night in the hopes that the Pequod will see them—they leap from the boat as the Pequod suddenly barrels towards them through the mist—their boat is crushed, and Starbuck’s men are saved.

top

The Hyena

Ishmael and his boat-mates laugh at their close call—Stubb, Flask, and Queequeg all report that this near death experience is quite typical—Ishmael recalls with some dismay that the man who almost got him killed, Starbuck, is considered a careful whaler—Ishmael drafts his will—Queequeg serves as his “‘lawyer, executor, and legatee.’”

top

Ahab’s Boat and Crew—Fedallah

Stubb and Flask discuss Ahab lowering his own whaleboat to hunt—generally, such a thing is not done—a captain at sea is as valuable as a general on a battlefield—Ahab’s plot is revealed—he smuggled his own private boat crew on the ship unbeknownst to Bildad and Peleg—he even modified his whaling boat for his peg leg—the Filipinos fit in with the crew quickly—new additions to whaling crews are common, with castaway creatures often being picked up—Fedallah does not fit in so well—Ishmael suggests that perhaps Fedallah is a product of demons consorting with humans.

top

The Spirit-Spout

The Pequod sails on peacefully—one night, Fedallah sees a “silvery jet” spurt out of the sea from afar—“There she blows!”—Ahab quickly demands that the sails be set, and the ship speeds off after the whale spout—the crew eventually lose sight of the spout, although everyone on board claims to have seen it at least one time—a few nights later, the spout appears again in the middle of the night and disappears out of sight—the spout reappears again night after night—supernatural omen of the presence of Moby Dick???—the eerily calm weather paired with the “spirit-spout” really creeps the crew out—eventually the weather turns stormy, which alleviates the superstitious tension but definitely does not boost anyone’s morale—the crew members strap themselves to the ship as they ride out the storm, but not Ahab—he plants his leg into his usual hole and stands, gazing into the violent storm, for hours and hours—very ominous—Starbuck later walks in on the captain asleep in a chair in his cabin…head thrown back and (closed) eyes pointing toward the compass hanging from the ceiling.

top

The Albatross

The ship reaches the Crozetts and runs into another whaling ship, the Goney (aka the Albatross)—the ship is bleached white like “the skeleton of a stranded walrus,” and it has streaks of red rust down its sides—the men on the ship look the worse for wear, and do not speak to anyone on the Pequod even though the ships pass so closely to one another—“Ship ahoy! Have ye seen the White Whale?”—the Goney’s captain tries to respond by speaking through his “trumpet” but accidentally drops it into the sea—he is unable to be heard without it… awkward—Ahab is unable to climb aboard the Goney because of the strong winds and is therefore unable to communicate with them—the two wakes of the ship cross, and small schools of fish that had previously been circling the Pequod swim over to the other ship’s flanks—Ahab takes this harmless sequence as a bad omen (“Swim away from me, do ye?”) and cries out to sail on.

top

The Gam

Ishmael further explains the strangeness of the encounter with the Goney—Ahab didn’t climb aboard the ship because of the weather, but it is suspected that he wouldn’t have climbed aboard anyway if the ship had answered that they hadn’t seen the White Whale—apparently, information regarding Moby Dick is all that Ahab cares about—this is a display of Ahab’s obsession because normally whaling ships are very social when they encounter one another—whaling ships have a special type of interaction called a “gam”—a gam is a social meeting between whaleships that allows for the captains and chief mates to board the other ship and mingle, which allows the two crews to socialize as well—one (strange) custom of a gam is the fact that the captains are left without anywhere to sit during the exchange, which forces them to remain standing—this proves to be very difficult, for the men can’t hold on to anything to keep their balance without looking undignified—of course, if the ship is rocked, the captain has to reach out for something to steady himself—Ishmael leaves us with the image of a captain seizing hold of the nearest sailor’s hair in order to save himself from going overboard during such an instance.

top

The Town-Ho’s Story

The Pequod encounters another ship—the Town-Ho—and this secret story is shared—the Town-Ho was sailing north when it springs a mysterious leak—the nasty Radney and the noble Steelkilt have at it—Radney orders Steelkilt to shovel pig crap (burn…) and Steelkilt smashes Radney’s jaw—a brawl breaks out—the captain locks Steelkilt and his supporters in the forecastle—lots of flogging—before Steelkilt gets his revenge on Radney, someone sees Moby Dick—the Town-Ho’s whaleboats lower to hunt Moby Dick—Moby Dick eats Radney! then escapes—the Town-Ho reaches a strange island and forces the natives to fix the leak—Steelkilt takes off in canoe—nobody knows where he ended up, and Radney’s widow still dreams about Moby Dick—“true story.”

top

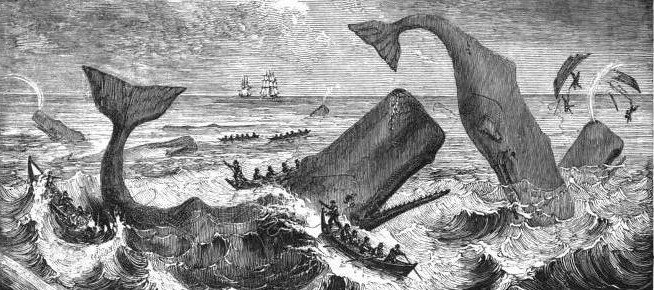

Of the Monstrous Pictures of Whales

Ishmael intends to illustrate “the true form of the whale, as he actually appears to the eye of the whaleman”—begins his dismissal of previous illustrations—“Hindoo,” Egyptian, and Greek depictions show whale incased in armor—Vishnu’s whale tale looks like an anaconda—disregard the whale depictions by Guido, Hogarth, and Sibbald—begins examining scientific illustrations of the Leviathan—circa 1671, Whaling Voyage to Sptizbergen produces plates depicting polar bears “running over [whale’s] backs”—circa 1793, “Picture of a Phseter or Spermaceti whale,” appears as a cyclopean creature—circa 1807, plate from Goldsmith’s Animated Nature depicts the whale as “an amputated sow,” and the narwhal—circa 1825, Bernard Germain, Count de Lacépède, all illustrations of various whale species appear incorrect—circa 1836, Frederick Cuvier’s Natural History of Whales: the sperm whale bears a strong resemblance to a squash—Ishmael addresses popular images of the whale—the whale’s proper shape can only be surmised at sea.

top

Of the Less Erroneous Pictures of Whales, and the True Pictures of Whaling Scenes

First, more monstrous depictions: Pliny, Purchas, Hackluyt, Harris, Cuvier—Four published outlines of Sperm Whale: Colnett, Huggins, Cuvier, and Beale—Beale > Huggins > Cuvier > Colnett—Beale’s whales appear mostly correct—Best depictions come from French artist Garneray, where “a noble Sperm Whale is depicted in full majesty of might,” and the Right Whale appears a “black weedy bulk”; “his jets are erect, full, and black like soot”—Ishmael speculates that Garneray was “either practically conversant with his subject, or else marvelously tutored by some experienced whaleman”—Ishmael mockingly compliments the French’s ability to depict the whale as they are as a people lacking in whaling ability—he commends a few sculptures of Greenland origin—goes into great depth on Durand’s depiction of contrasting whaling images.

top

Of Whales in Paint; in Teeth; in Wood; in Sheet-Iron; in Stone; in Mountains; in Stars

Ishmael begins by illustrating an amputee beggar holding the depiction of his amputation’s circumstance—“his three whales are as good as were ever published Wapping, at any rate; and his stump as unquestionable a stump as any you will find”—in many whaling towns, depictions of whales will found engraved onto whale teeth—done with some dental materials but mostly whalemen’s “jack-knives”—Ishmael compares the whaler to the savage, as they had been removed from Christendom—Ishmael likens the tooth carvings to Hawaiian war paddles, Achilles’ shield (see Homer’s Iliad), and the prints of Albrecht Dürer—discusses small wood carvings, brass knockers, and weather-cocks in the shape of the Leviathan—cautions those who wish to see the whale in person.

top

Brit

Brit: “the minute, yellow substance,” which provides food for the baleen, right whale—Right Whales swim “sluggishly” and slowly in order to “advance their scythes through the long wet grass of marshy meads”—Ishmael continues the comparison of right whales to mowers, citing especially the noise they produce during their swimming—the whale float and appear as islands from afar—Are animals in the sea like those on land? Can the great white shark be compared to the dog?—Noah’s flood has not receded: “two thirds of the fair world it yet covers”—the land and the sea is an “analogy to something in yourself.”

top

Squid

Daggoo spots an unidentified “white mass” rising from and falling below the surface of the sea—it rises again, and Daggoo cries out: “There! there again! there she breaches! right a head! The White Whale, the White Whale!”—Ahab eagerly orders to launch the whaleboats—the white mass sinks and rises again—finally, recognition is made; the creature has “innumerable long arms radiating from its centre, and curling and twisting like a nest of anacondas”—Starbuck: “Almost rather had I seen Moby Dick and fought him, than to have seen thee, thou white ghost!”—Flask: “what was it sir?”—Starbuck: “The great live squid”—Ahab turns his whaleboats back toward the Pequod—it is suspected that the giant squid provides the sperm whale “his only food”—whalemen have seen whales disgorge squid tentacles—Ishmael speculates that the giant squid may have been the source the mythological Kraken.

top

The Line

“I have here to speak of the magical, sometimes horrible whale-line”—originally made of hemp, “slightly vapored with tar, not impregnated with it”—the hemp is more pliable and more convenient for the sailor to use—the tar, however, adds no durability—in the American fishery the Manilla rope now reigns supreme—Manilla rope is not as durable as hemp but far stronger, softer, and more elastic—racist remark that “hemp is a dusky, dark fellow, a sort of Indian; but Manilla is as a golden-haired Circassian to behold”—the whale-line is two-thirds an inch in thickness—“one in fifty yarns will each suspend a weight of one hundred and twelve pounds”—the strength of the whole line will hold nearly three tons—about two hundred fathoms long—fathom is six feet—the lines coil in massive humps; uncoiling can take up a whaleman’s entire morning—English boats carry two lines and two smaller tubs rather than the large one in American boats—before lowering for a chase the line is drawn round logger head for the entirety of its length—the whale line covers the boat in “complicated coils”—never can you not be wary of the coil under you—many have been pulled asunder by its “perilous contortions.”

top

Stubb Kills a Whale

Queequeg suggests that a sperm whale will soon be spotted because of the squid sighting—a “spell of sleep” falls over the Pequod because of the seemingly “vacant sea”—a sperm whale brings the crew out of its daze—the boats lower and Stubb and Tashtego kill the beast—its blood “shot into the frighted air […] as if it had been the purple lees of red wine.”

top

The Dart

Ishmael explains the activities of the harpooner while in pursuit of a whale—they row, they run, they trample the others, they harpoon the whale—“all this is both foolish and unnecessary”—Ishmael proposes that the harpooner stay in the bow throughout the trip and be exempt from rowing—“To insure the greatest efficiency in the dart, the harpooneers of this world must start to their feet from out of idleness, and not from out of toil.”

top

The Crotch

“The crotch […] is a notched stick of a peculiar form […] for the purpose of furnishing a rest for the wooden extremity of the harpoon”—two harpoons rest in the crotch, ready for the harpooner—the second harpoon (aka iron) dangles dangerously overboard after the first is launched into the whale—especially dangerous when many whaleboats are present.

top

Stubb’s Supper

The crew slowly pulls the whale back toward the boat—Ahab seems dissatisfied and retires to his cabin—Stubb cannot contain his excitement—Daggoo cuts him a whale steak at his request—Fleece cooks it for him, and Stubb feasts by lantern light—he finds the steak “too tender” and complains to Fleece—he tells Fleece to preach to the sharks as they ravenously feast on the whale carcass—“Give the benediction, Fleece, and I’ll away to my supper.”—Fleece doesn’t preach to sharks properly, according to Stubb, who urges the old cook to preach in a different manner—Fleece tries again: “Fellow-critters, I don’t blame ye so much for; dat is natur, and can’t be helped; but to gobern dat wicked natur, dat is de pint.”—Fleece finishes his mandated sermonizing, and Stubb berates him again about the steak and lectures him about eternity—Fleece eventually departs—“Wish, by gor! whale eat him, ‘stead of him eat whale. I’m bressed if he ain’t more of shark dan Massa Shark hisself.”

top

The Whale as a Dish

Most whalemen don’t eat whale meat—“this seems so outlandish a thing,” Ishmael remarks, “that mortal man should feed upon the creature that feeds his lamp”—centuries old accounts of French and English consumption of whale—porpoise meat is sometimes eaten when prepared as meatballs—Eskimos (“Esquimaux”), by contrast, use every part of the whale—whale meat is fatty, like the rest of the creature—“In the case of a small Sperm Whale the brains are accounted a fine dish.”—Ishmael contemplates the morality of eating a creature freshly killed—“Who is not a cannibal?”—He suggests that island cannibals will have more grace on Judgment Day than those who eat foods made available by animal cruelty (“pate-de-fois-gras”).

top

The Shark Massacre

The removal of the blubber from a freshly caught whale is usually left as a duty for the next morning, unless sharks are about, in which case “little more than the skeleton would be visible by morning”—the sharks must be beaten off with whaling spades—the animals have “wondrous voracity”—when the whaling spades make gashes in the sides of the sharks, their entrails spill out—“[t]hey viciously snapped, not only at each other’s disembowelments, but like flexible bows, bent round, and bit their own”—Queequeg nearly loses an arm in the chaos—“de god wat made shark must be one dam Ingin.”

top

Cutting In

Sabbath day, but the Pequod’s crew is at work—“Ex officio [by virtue of one’s position or status] professors of Sabbath breaking are all whalemen.”—lots of butchery going on—sacrifices to the “sea gods”—the work of “cutting in” proceeds as follows: 1) hoist the cutting tackles (“a cluster of blocks generally painted green”) up the mainmast and fasten to the lower masthead; 2) secure the cutting tackles to the windlass (remember? the device that hoists the ship’s anchor), and attach the blubber hook (“weighing some one hundred pounds”); 3) suspend blubber hook over the side of the ship, over the carcass of the whale; mates employ long spades to gouge a hole “just above the nearest side fin”; 4) make a semicircular cut around the hole, making the beginning of the “blanket” pieces (like peel a gigantic torpedo-shaped orange); 5) insert the blubber hook into the hole dug by the mates; 6) singing aloud while working the windlass to hoist the blubber hook—the ship pitches to one side as the crew strains at the windlass— “a startling snap is heard,” and “with a great swash” the ship rights itself, as the blanket begins to “spiralize” off the whale’s body, turning over and over in the water as the blubber hook is slowly brought higher and higher—the mates keep at their work with the lances, meanwhile, making cuts in the whale’s body; “scarfing” is like perforations in paper—when the blubber hook can be raised no higher, the crew stops working the windlass—the heavy, bloody mass swings precariously, and the crew has to take care not to be knocked overboard by it—a harpooneer cuts a hole in the lower portion of the blanket piece with a “boarding-sword,” where another blubber hook is attached—then the harpooner (“this accomplished swordsman”) cuts away the blanket piece, “with a few sidelong, desperate, lunging slices”—the blanket piece now freed from the whale’s body is lowered into “an unfurnished parlor” below deck called the blubber-room—the crew at the windlass and the lance-armed mates start cutting away the next blanket piece by the same process—“And thus the work proceeds; the two tackles hoisting and lowering simultaneously; both whale and windlass heaving, the heavers singing, the blubber-room gentlemen coiling, the mates scarfing, the ship straining, and all hands swearing occasionally, by way of assuaging the general friction.”

top

The Blanket

Ishmael ponders “what and where is the skin of the whale?”—debated the matter with both “whalemen afloat” and “learned naturalists ashore”— all aflutter trying to reckon whether the skin of the whale is distinguishable from its blubber, which has “the consistence of firm, close-grained beef”—blubber ranges in thickness from 8 or 10 to 12 or 15 in.—and what would be “the outermost enveloping layer of any animal, however dense, if not his skin?”—but there’s a “thin, transparent substance” enveloping the blubber of the whale—“the skin of the skin, so to speak”—it’s a sort of isinglass (OED: “a firm, whitish semitransparent substance […] obtained from the air-bladders of some fresh water fish, especially the sturgeon”)—substance “contracts and thickens […] becomes hard and brittle” when dried—Ishmael has specimens of this dried whale skin pressed between the pages of his whale books, serving as bookmarks—fancies that the dried skin exerts a magnifying effect—“it is pleasant,” Ishmael muses, “to read about whales through their own spectacles”—but how could the skin of a creature so “tremendous” as the whale be “thinner and more tender” than that of a newborn child?—“no more of this”; okay…—“assuming the blubber to be the skin of the whale”: okay…—the large quantities of oil extracted from the blubber (roughly 100 barrels from a large Sperm) should give a fair appreciation of the “enormousness” of the whale’s living body—Ishmael now turns his attention to the appearance of the whale’s outer layer—spread all over with “numberless straight marks in thick array”—like engravings, not upon the isinglass, but seen through it—they’re “hieroglyphical,” and like some hieroglyphs remain “undecipherable”—Ishmael reflects that these markings are very like those observable on coastal rock faces—you see these markings in large, full grown bull whales, so Ishmael guesses that they’re produced by hostile contact with other whales—the blanket of the whale is aptly named because it keeps the creature warm in icy waters (duh)—while certain other creatures dwell Hyperborean waters, it’s more remarkable in the case of the whale since it’s warm-blooded—“It does seem to me,” Ishmael says, “that herein we see the rare virtue of strong individual vitality, and rare virtue of thick walls, and the rare virtue of spacious interiors.”—concludes by exhorting his fellow man to model himself after the whale: “in all seasons [retain] a temperature of thine own.”

top

The Funeral

All the blubber has been stripped from the dead, beheaded whale—carcass changed in color but still “colossal”—floats farther and farther away behind the “almost stationary ship” surrounded by sharks and seabirds, all feeding on it—din of the animals feeding on can be heard for hours after cutting carcass loose—“There’s a doleful and most mocking funeral!”—ironic that Ishmael remarks the “horrible vulturism of earth” upon describing this sight after so lovingly describing all the butchery conducted by man to bring a whale to this end—never mind, not quite the end—Ishmael describes the circumstance of a “vengeful ghost” of the whale—sometimes a floating whale carcass is spotted afar by passing ships—no whaleships, they’d know, but “timid man-of-war or blundering discovery vessel”—white in the sunlight, sea spray dashing up its sides, birds congregated above it, the carcass is noted in the ship’s log as a shoal or some other dangerous formation—caution is urged—records taken, shared with other ships and made part of the navigational knowledge of the sea—so it happens, for years maybe, that ships will avoid the spots where whale carcasses have been so mistook—“There’s your law of precedents,” Ishmael says, mocking the sometimes futility of human knowledge, “there’s your utility of traditions”—something fitting in the whale’s body, a “real terror” to man in life becoming a “powerless panic” to him in death—“There are other ghosts than the Cock-Lane one, and far deeper men than Doctor Johnson who believe in them.”

top

The Sphinx

Ishmael’s like, “Oh, yeah, did I say that that whale was beheaded? Let’s go back a bit.”—beheading a Sperm is a “scientifically anatomical feat”—first difficulty: whales don’t really have necks—second difficulty: “surgeon” must perform his operation 8-10 ft. above the whale’s carcass, from the side of a pitching ship no less—third difficulty: whale’s spine has to be severed at the precise point where it joins the skull, many feet deep in the flesh, so the whaleman is working blind—Stubb boasts that he can perform this delicate operation in 10 min.—beheading the first operation performed when a whale is brought alongside a ship—head just hangs astern while the body is stripped—afterwards, if the head of a small whale, it’s brought on deck to be dealt with—not so easy with full grown Sperm, whose head is “one third of his entire bulk”—can’t even be lifted aloft by the ship’s tackle—whale’s head the Pequod is dealing with presently is hoisted against the ship, bobbing in the sea—still leaning the whole ship to one side—“there, that blood-dripping head hung to the Pequod’s waist like the giant Holofernes’s from the girth of Judith.”—it’s noon: the Pequod’s crew breaks for lunch below, and the once boisterous deck is silent—enter Ahab—takes a few turns on his quarter-deck, grabs Stubb’s “long spade” (the decapitation tool), sticks the spade into the whale’s head still dangling astern, sticks the handle under his arm, and so leans overboard, gazing into the head of the whale—starts talking to it, a “black and hooded head” Ishmael compares to the Sphinx’s, asking it to talk: “‘Speak thou vast and venerable head’”—Ahab wants to know the “secret thing” in the head—the head has sounded to the world’s deepest places, “‘[w]here unrecorded names and navies rust, and untold hopes and anchors rot’”—this “‘awful water-land’” is the whale’s “‘most familiar home’”—Ahab imagines tragic human scenes (lovers drowning together after leaping from a flaming ship, a “murdered mate” tossed overboard by pirates) that the head has witnessed—so much the whale has seen will forever remain unknown and unrecorded because, supposes Ahab, “‘not one syllable is thine!’”—“‘Sail ho!’”— interview interrupted by the announcement of a passing ship—Ahab straightens up, clears the “thunder-clouds” from his brow—“‘Well, now, that’s cheering.’”—does seem genuinely relieved by the unexpected gam, but the source of his “deadly calm” and “breezlessness” not so easily dispelled.

top

The Jeroboam’s Story

Ship draws near—mastheads spotted by glass show her to be a whaler—ships in the American Whale Fleet outfitted with unique signal flags to recognize each other asea—thus the Pequod meets the Jeroboam of Nantucket—Jeroboam lowers a boat—Starbuck makes to send the side ladder down but is waved off— “malignant epidemic” aboard says Jeroboam captain, Mayhew—Mayhew and his boat unaffected but worry about infecting the Pequod—won’t come aboard but can still communicate, with difficulty—winds pick up, and Mayhew’s rowers work hard to keep boat within hailing distance—among these rowers a man of “singular appearance”—“small,” “short,” “youngish,” “freckles,” “redundant yellow hair,” “cabalistically-cut coat of a faded walnut,” overlong sleeves rolled up to the wrists—“A deep, settled, fanatic delirium was in his eyes.”—Stubb recognizes him, someone the Town-Ho crew told him about—dude has some strange power over the Jeroboam’s crew—“He had been originally nurtured among the crazy society of Niskyeuna Shakers”—after some spiritual shenanigans with that lot, he made for Nantucket—joined the Jeroboam’s crew as a “greenhand candidate” (like Ishmael)—ashore he kept a “common sense exterior,” but once asea his “insanity broke out”—announces himself the “arch-angel Gabriel,” tells the captain to jump overboard, and publishes his manifesto—Gabriel a god at sea—cray, but an “ignorant” crew invests him with “sacredness” (like Ahab?)—wanting to be rid of him, Mayhew plans to leave him at the nearest port—Gabriel promises “perdition,” and crew demands that Mayhew keep Gabriel aboard—dude refuses to work but he has “complete freedom of the ship”—has become even more powerful since the epidemic, because it’s at his command—many among the Jereboam’s crew (“mostly poor devils”) tremble before Gabriel like a god—ok, back to the Pequod—Ahab to Mayhew: “I fear not thy epidemic, man.”—invites Mayhew aboard again, and Gabriel starts shouting about plagues—Mayhew goes to talk down Gabriel, but his words are lost by a swell that carries their boat out of range—boat rowed back—Ahab: “Hast thou seen the White Whale?”—Gabriel starts shouting about a stove whale-boat and a “horrible tail”—Mayhew starts trying again to shut him up—boat taken out of range again by some “riotous waves”—Gabriel warily eyes the decapitated sperm whale’s head dangling astern the Pequod—Mayhew reports a story about Moby Dick to the Pequod with frequent interruptions from Gabriel—Jeroboam crew learned of Moby Dick after setting off, Gabriel had discouraged the captain from pursuing him—said the whale was “the Shaker god incarnated”—two years later, Macey, mate of the Jeroboam, spots Moby Dick and lowers a boat after him anyway—Gabriel’s atop the masthead shouting out prophecies of doom—Macey’s at the head of the boat shouting back about killing Moby Dick—then a “white shadow rose from the sea”—knocks the breath out of the oarsmen, knocks Macey fifty yards out to sea—he “forever sank”—Ishmael notes: “fatal accidents” like this can sometimes happen in the whale fishery—Macey’s death = Gabriel’s prophecy fulfilled, so now he’s got “added influence”—“He became a nameless terror on the ship.”—Ahab interviews Mayhew about how to track down Moby Dick—Gabriel makes more dire prophecies concerning Ahab—Ahab ignores him but remembers he’s got a letter for Mayhew, sends Starbuck after it—Ishmael explains that it’s common for whaleships to carry post for other whaleships on the off chance they meet at sea—Starbuck returns with the letter, but its all wet and moldy—Ahab’s tries to make out the “dim scrawl” on the letter while Starbuck makes a notch in a lance to deliver the letter to Mayhew’s boat—turns out the letter’s for the dead mate, Macey, and from his wife (Ahab guesses) by the “pinny hand” of the address—Mayhew: “‘Poor fellow! poor fellow!’”—Gabriel suggests Ahab keep the letter since he’s “‘soon going that way’”—Ahab screams at Gabriel and goes to deliver the letter to Mayhew—Mayhew’s boat drifts in such a way that Gabriel grabs the letter instead—impales it on a knife and throws it back to the Pequod, where it sticks in the deck at Ahab’s feet—Gabriel orders the boat to row away, back to the Jeroboam—the Pequod’s crew gets back to work on their dead whale—meanwhile “many things were hinted in reference to this wild affair.”

top

The Monkey-Rope

Processing a whale has people running this way and that all over the ship, so Ishmael’s scattered trying to describe the scene—“Did I even even mention how the blubber hook gets inserted into the hole carved by the mates?”—well, Queequeg did it, it being the job of the lead harpooneer generally—harpooner stands astride the dead whale’s back during the stripping operation—the whale’s body being almost entirely submerged—Ishmael’s Queequeg’s bowsman (“the person who pulled the bow oar in his boat”), so it’s his job to assist Queequeg in his “hard-scrabble scramble” on the dead whale’s back—does so by means of “the monkey-rope”: a safety line tethering the harpooneer to the ship—two men literally attached at the hip, the monkey-rope secured to each of their belts—“wedded,” Ishmael says—“usage and honor” demand that if Queequeg drown, Ishmael go with him—“So, then, an elongated Siamese ligature united us. Queequeg was my own inseparable twin brother…”—gazing down at Queequeg, Ishmael thinks he’s forfeited his individuality and free will—periodically he has to jerk on the monkey-rope to pull Queequeg from between the body of the whale and the side of the ship—further reflects that all mortals are in a similar situation as him and Queequeg—we all, in “one way or other, [have] this Siamese connexion with a plurality of other mortals”—footnote reveals that while all whalers feature a monkey-rope, it’s an “improvement” unique to the Pequod, devised by Stubb, to fasten the rope to the man aboard—another hazard Queequeg faces here is sharks, attracted by the bloody mess of stripping the whale—keeps them at bay with his feet—Ishmael note: sharks rarely attack humans—an added protection: Tashtego and Daggoo lean over the side of the ship, stabbing at the sharks with long spades—security measure that could be more threatening to Queequeg than the sharks—Queequeg can only pray to Yojo and leave his life in the hands of his gods—like all whalemen must—“But courage!”: Queequeg finally returns a dripping and trembling mess with some consolation in store—a refreshing beverage—“what? Some hot Cogniac? No!”—“a cup of tepid ginger and water”?!—Stubb smells the ginger on the air and takes the cup from Queequeg’s hand before he’s had a chance to drink it—scolds Dough-Boy, the steward, for thinking ginger and water could stoke mighty Queeweg’s fire—“‘There is some sneaking Temperance Society movement about this business,’” he complains—confronts Starbuck about it—Starbuck agrees lamely that it’s “‘poor stuff enough’”—Stubb keeps railing on Dough-Boy, who finally reveals that Aunt Charity told him not to serve the harpooneers spirits but the ginger concoction instead—“‘ginger-jub…so she called it’”—Stubb smacks Dough-Boy, sends him running—Starbuck tells Stubb to go get what drink he wants for Queequeg himself—he returns with a flask full of spirits for Queequeg and “a sort of tea-caddy” containing the “ginger-jub” ingredients—throws “Aunt Charity’s gift” into the sea.

top

Stubb and Flask Kill a Right Whale; And Then Have a Talk Over Him

More to say about that whale’s head hanging over the side of Pequod, but not just now—drifting ship’s come into the vicinity of right whales, as told by the presence of “yellow brit” in the water—whalers don’t usually bother with these “inferior creatures,” but the crew’s ordered to kill a right whale—not even done processing the sperm whale attached to the ship!—Stubb and Flask soon have boats lowered in pursuit of the “tall spouts” of some right whales—get so far out to sea that the mast-heads can barely see them—commotion spotted in the distance and then the boats are being towed toward the ship by the harpooned whale—whale sounds a short distance from the hull (Ishmael thought for a moment “he meant it malice”)—boat crews haul in the right whale after some hazardous maneuvering round and round the Pequod—Stubb and Flask stab him with their lances—right whale expires, “with a frightful roll and vomit”—Stubb and Flask have a chat while hauling in their kill, mostly concerning their concerns about Fedallah—Stubb: what’s Ahab want with this “‘lump of foul lard?’”—Flask: haven’t you heard that a ship that’s had a sperm whale’s head hoisted to one side and a right whale’s head on the other can never capsize?—Stubb: ?—Flask: idk, heard Fedallah talking about it; don’t you think he’s sketchy?—both mates are wary of the man—Flask wonders about Ahab’s connection to him—Stubb thinks Ahab’s made a deal with the “‘devil in disguise’” to catch Moby Dick—Stubb talks big about beating up Fedallah, yanking off his tail, etc.—Flask points out the empty nature of these threats if Fedallah is indeed the devil—the witty repartee goes on until they’ve hauled the right whale to the ship—Flask: see, now we’ll see this whale’s head hoisted opposite the sperm whale’s—indeed this happens—the ship is thus given an even keel—Ishmael: “So, when on one side you hoist Locke’s head, you go over that way; but now, on the other side, hoist in Kant’s you come back again; but in a very poor plight.”—just throw them both overboard, thinks he, if you want an even keel—processing right whales a lot like processing sperm whales—except with right whales “the lips and tongues are separately removed and hoisted on deck,” whereas the sperm whale’s head is cut off whole—not so in this case—whales’ bodies are dropped astern and ship proceeds with their heads dangling to each side—like “a mule carrying a pair of overburdened panniers”—Fedallah calmly eyes the right whale’s head, looking from it to his hand—chances to stand in Ahab’s shadow, so that his shadow elongates Ahab’s—crew toils on, quietly speculating about these happenings.

top

The Sperm Whale’s Head: Contrasted View

Got two great whale’s heads here, let’s put our own down with them—sperm and right whales only two hunted species—to Nantucketers, represent the “two extremes of all known varieties of the whale”—most differences observable in the head, so let’s compare—“practical cetology”—“mathematical symmetry” to the sperm’s head, right lacks = “pervading dignity”—whale heads, like humans’, get salt and peppery with age—present sperm a “‘grey-headed whale’”—least dissimilar in the heads is the placement of the whales’ eyes: low on the side of the head near the hinge of the jaw—whales can’t see straight ahead or straight behind—like having your eyes where your ears reside—given the hugeness of the head that resides between the eyes, Ishmael conjectures that they must send two separate images to the brain: one of the world to the left side, one of the world to the right, all between “darkness and nothingness”—humans can barely look carefully at any two things at once, how must it be for the whale?—“is his brain so much more comprehensive, combining, and subtle than man’s”?—attributes the erratic movements of pursued whales, their “timidity and liability to queer frights,” to their “diametrically opposite powers of vision”—on to the ear: hard to find—features no “external leaf,” hole so narrow that you can stick a quill in it—(it’s lodged behind the eye)—sperm whale ears have external openings, but those of right whales are covered with a membrane—look now down the sperm whale’s mouth, “from floor to ceiling lined, or rather peppered with a glistening white membrane, glossy as bridal satins”—look upon the jaw—whaleman impaled not taking care around its “rows of teeth”—Ishmael remarks how live sperms can be seen with their jaws hanging open at right angles to their bodies—supposes them “dispirited,” “hypochondriac,” “supine”— sperm whale’s jaw unhinged and deprived of its teeth to furnish sailors with scrimshaw material—harpooneers, “accomplished dentists,” extract the teeth—jaw bone lashed to the deck and teeth removed by means of tackle suspended from rigging—“generally forty two teeth in all”—no cavities in whales’ teeth, even old ones—after extraction, jaw bone sawed into slabs and piled away like building joists.

top

The Right Whale’s Head: Contrasted View

Having a gander now at the right whale’s head—looks like a big “galliot-toed shoe” where the sperm’s looks more like a “Roman war-chariot”—Dutch voyager once likened its shape to a shoemaker’s last—looks different depending on what angle you view it from—from “two f-shaped spout holes” looks like an “enormous bass viol”—from the “strange, crested, comb-like incrustation” atop the head (the “crown,” per Greenlanders or “bonnet,” per Southern fishers of the right whale) looks like a big oak tree—crabs nest in the bonnet—if a crown, right whale makes for a pouty looking king—“hanging lower lip” is some 20 ft. long and 5 ft. deep—whale yields 500+ gal. oil—mouth interior vast (“is this the road that Jonah went?”), “roof” some 20 ft. high—Ishmael contemplates the whale’s baleen: “those wondrous, half vertical, scimitar-shaped slats of whale-bone, say three hundred on a side […] edges […] fringed with hair fibers”—right whale filters its food (brit and small fish) from the sea through these “Venetian blinds”—“curious marks” on the central blinds reckoned by some whaleman to record the whale’s age—Ishmael relates how the whale’s baleen was described in “old times”: “‘hogs’ bristles,’ ‘fins,’ ‘whiskers,’ ‘blinds,’ whatever—material used to fashion the busks (stiffening strips) of some women’s garments, so they’re moving about “gaily, though in the jaws of the whale”—the fashion of whalebone busks waning—material still used to make umbrellas—one last comparison of the baleen to a pipe organ—regard now the tongue: “glued […] to the floor of the mouth […] fat and tender […] apt to tear […] hoisting it on deck”—tongue processed as store of oil—summary of whale head comparison: sperm whale head features toothed mandible-like jaw, sperm reservoir, one spout, almost no tongue; right whale head features “blinds of bone” (baleen), lower lip, no oil reservoir, two spouts, oil-rich tongue—at last look, before the heads are dropped into the sea, the sperm whale’s head appears a Platonist, the right whale’s a Stoic.

top

The Battering-Ram

Ishmael considers the sperm whale’s head in its “front aspect” for what “battering-ram powers” it might possess—teaser: “one of the most appalling, but not the less true events, perhaps anywhere to be found in all recorded history”—observes that all the sperm whale’s vital features (eyes, “nose”/spout-hole, mouth, etc.) are well out of the way of his prodigious forehead—“a dead, blind wall,” with no bone to be found in it either—“one wad”—blubber wrapping the sperm whale’s head tougher than elsewhere on the animal, repels the “severest pointed harpoon”—analogy to the fenders (or bumpers) used on ships to avoid damaging contact with other ships/objects: don’t use hard stuff, rather pliant but still tough stuff—Ishmael fancies the honeycomb-like structures inside the whale’s head communicate with the outer air, expanding or contracting so to be more and less plaint, at will—a treasure-trove of “life” resides behind this “dead, impregnable, uninjurable wall,” and “this the most buoyant thing within” (it’s spermaceti, y’all)—don’t be surprised at the awesomeness of the whale after I’ve described it to you, says Ishmael.

top

The Great Heidelburgh Tun

“Now comes the Baling of the Case,” meaning: extracting the stores of spermaceti from the sperm whale’s head—got to know first about its “curious internal structure”—split the “solid oblong” of the whale’s head into two “quoins” (quoin, naut. = wedge comprised of one flat and one slopping side, like the device used to stop open doors)— lower quoin all boney (cranium, jaw, etc.); upper quoin free of bones, “unctuous mass”—now horizontally subdivide the upper portion into two parts, separated in the living animal by a tendon-like substance—upper part = “the junk” = “one immense honeycomb of oil,” comprised of many cells separated by a complex weave of “elastic white fibres”—lower part = “the Case” = met., “the great Heidelburgh Tun of the Sperm Whale”—Heidelburgh Tun refers to a gigantic cask in the German city always replenished with the finest wine—the case of the sperm whale contains “by far the most precious of all his oily vintages,” i.e. spermaceti—the “highly-priced” substance in its “absolutely pure, limpid, and odoriferous state”—begins to solidify when exposed to the open air—case affords about 500 gal. of sperm, but some of that lost in the extraction process—Ishmael can’t say what the Heidelburgh Tun was coated in, but it can’t have been as lovely or rich as the “inner surface” of the case: a “silken pearl-colored membrane”—an 80 ft. sperm whale provides a case about 26 ft. in depth, when hoisted vertically aside the ship—the whaleman decapitating the whale must take care not to rupture the case—complex network of ropes and tackle required to suspend vertically the decapitated head out of the water enough to commence extracting the spermaceti—an “almost fatal operation” “in this particular instance.”

top

Cistern and Buckets

Tashetego gracefully walks out upon the rigging and tackle suspending the sperm whale’s head aside the ship—carries a small tackle called the “whip”: a rope passing through a wood block—connecting the whip to the cutting tackle, hands one end of the rope to a shipmate and descends the other end to alight upon the head of the whale—shipmate hands him a short-handled spade with which he begins carefully prodding the head to break into the Tun/case—an iron-bound well-bucket meanwhile attached to the whip—secured by two or three men aboard deck, the bucket is lowered into the Tun, guided by Tash by means of a long pole pressed upon the bucket’s bottom—on Tash’s command, bucket raised from the depths of the Tun full to the brim of spermaceti—“all bubbling like a dairy maid’s pail of new milk”—grabbed by an “appointed hand,” bucket emptied into a large tub on deck—process repeats until the Tun yields no more—guiding pole will descend 20 ft. into the head of the whale before job’s done—Pequod’s crew been at this work for a while—many tubs filled with spermaceti when “a queer accident happened”—not clear whether Tash got reckless, or the whale’s head was particularly slippery, or the devil himself made it happen—either way, as the 18th or 19th bucket was being raised from the depths of the Tun, Tashtego feel headfirst down into the oily depths, “clean out of sight”—Daggoo cries “Man overboard!” and swings down to the head, foot in the bucket—meanwhile the formerly lifeless head throbs and heaves all over, as Tash struggles inside—“as if at that moment [the head was] seized with some momentous idea”—one of two blubber hooks securing the head to the tackles rips free with the added weight of Daggoo on the head—weight of the swinging head rocks the entire ship—Daggoo tries to cram the bucket back down the hole for Tash to grab ahold of, and Stubb scolds him for it—“Stand clear of the tackle!”—other blubber hook rips out—Daggoo lifted aloft still holding onto the tackles—head drops into the sea and sinks with Tash still inside—the splash made by the head hasn’t even settled when a naked figure with a sword in its hand is seen diving over the bulwarks—Queequeg is going after Tash—crew stares powerlessly down at the sea where the head and Queequeg vanished—from his lofty perch, Daggoo announces the reappearance of both men above the surface of the water—Queequeg swims Tash to a boat that had been lowered—Tash takes a while coming to; Queequeg looks a bit rough—means of rescuing Tash, obviously later reported to Ishmael, are given as follows: Queequeg swam down after the head, used the sword to cut a large hole in its side, thrust his arm inside, and pulled Tash out—first Queequeg got ahold of Tash’s leg; had to flip him around to deliver him headfirst from the head—“great skill in obstetrics of Queequeg”—why wonder? people fall into wells reasonably often, and this whale’s head was super slippery—but why did it sink so rapidly?—having been emptied of nearly all its sperm, the head had lost most of its characteristic buoyancy—“dense tendionous wall” of the case would have made it sink like lead, but enough of the lighter substances were still present to have the head sink “slowly and deliberately” for Queequeg to perform his delivery—if Tash had died, one can hardly imagine a sweeter end—“smothered in the very whitest and daintiest of fragrant spermaceti; coffined, hearsed, and tombed in the secret inner chamber and sanctum sanctorum of the whale.”

top

The Prairie

No phrenologist felt the bumps on Leviathan’s head, no physiognomist scanned the lines of his face—“Such an enterprise would seem almost as hopeful as for Lavatar to have scrutinized the wrinkles on the rock of Gibralter, or for Gall to have mounted a ladder and manipulated the dome of the Pantheon.”—famed physiognomists (Lavatar) and phrenologists (Gall and Spurzheim) do apply their theories to other species than man—Ishmael pioneers, applies the two pseudo-sciences to the whale—“[p]hysiognomically regarded,” sperm whale “anomalous” because no nose—nose usually makes the face (as a phallic structure does a landscape garden) but would’ve been “impertinent” to the whale—the “full front of his head” though, “sublime”—foreheads of humans and animals alike “grand,” “majestic,” recording as it were before God the works of our days—few human foreheads (exception: Shakespeare’s) broad enough to show the pathways of their thinking, like the tracks animals make descending hillsides for nourishment—a “mere strip” in most creatures, forehead of the whale colossal—viewed in its front-most aspect gives no token of a face even—“god-like dignity inherent in the brow is so immensely amplified, that gazing on it, in that full front view, you feel the Deity and the dread powers more forcibly than in beholding any other object in living nature”—regarded in profile, whale’s forehead reveals a “depression” near its middle = per Lavatar, “mark of genius”—neither writer nor orator, whale’s genius shown in his silence—Egyptians deified the crocodile for having no tongue—if reverting back to pagan worship, count the sperm whale among the gods—having experimented with it, physiognomy = “passing fable”—no deciphering the hieroglyphically markings on every being’s face—learned physiognomists can’t read the face of a peasant, how can Ishmael hope to succeed in reading the brow of the mighty whale?

top

The Nut

Now for the phrenological experiment—whale’s brain = “geometric circle […] impossible to square”—full grown Sperm has 20ft. skull—featuring a flat base and a steadily inclining top plane—high end of skull features “crater,” where reposes the junk and sperm—beneath crater, in a cavity about 10 in. long, resides the whale’s brain—at least 20 ft. from forehead—whale’s brain so fortified that some whalemen deny its existence—can’t see or feel indications of his “true brain”—emptied of stores of junk and sperm and regarded from behind, whale’s skull looks like a human’s—shrunk down and placed among human skulls it would be hard to pick out—phrenologist might say: “This man had no self-esteem, and no veneration.”—phrenologists err not extending studies to the spinal column—regard vertebrae as so many mini-skulls—better to feel a spine for indications of character than a skull—applying this “spinal branch of phrenology” to the whale: uniquely, “spinal canal” retains considerable dimensions (approx. 10 in. across, 8 in. high) in relation to skull before it begins to taper—mystery of the smallness of the whale’s brain in comparison to his body might be resolved by considering the uncommon girth of his spinal chord—leaving this “hint” to the phrenologists to ponder—finally, let’s talk about the sperm whale’s hump—“rises over one of the larger vertebra” so is “the outer convex mold of it”—phrenological speculation of the “spinal branch”: hump = “organ of firmness or indomitableness in the Sperm Whale.”

top

The Pequod Meets the Virgin

Pequod meets the German ship Jungfrau (Virgin) of Captain Derick De Deer—they are an empty vessel (or “clean one”) —no oil to fuel their lamps and they’ve come begging—their need fulfilled, they begin the journey back to their ship when they spot eight whales afar, one is missing a fin—the German boats turn their attention to these whales and the Pequod sends out their boats—The whaleboats from the Pequod quickly overtake the Germans with the exception of Captain De Deer’s boat—De Deer mocks the Nantucketers with his can of oil, which only fuels them—in efforts to lighten his load, De Deer throws the lamp-feeder from the boat—the German’s boat gets stalled for a moment and the Nantucket boats catch even—as the German harpooners are about to strike, Queequeg, Tashego, and Daggoo together throw their harpoons and get the whale fast—simultaneously the Nantucket boat crashes into the German boat, throwing them into the water—the whale sounds, Queequeg, Tashego, and Daggoo hold tight until it exhausts itself underwater—when surfaced, they commence the routine of getting the whale pieced out—they find an old infected wound on the whale, swelling and discolored—Flask makes an incision before “humane Starbuck” could stop him—this caused the whale to die in agony and the swell exploded and covered them in this material—Starbuck ties up the whale—they begin cutting into the whale and find objects within like a harpoon in the old wound and a stone lance—the huge carcass begins to pull the ships down, they eventually have to cut it loose and let it sink—this happens on occasion but sperm whales usually float—Jungfrau spots another whale but the Pequod recognizes that it’s just a Fin-Back and decide it’s not worth the pursuit.

top

The Honor and Glory of Whaling

Ishmael finds time in his busy whaling schedule to contemplate how his whaling stories compare to that of whales in literature—his first comparison includes the Perseus and Andromeda story where the princess is, of course, saved from the monster by the ever so heroic Perseus, and a skeleton was found within the monster he slew—Ishmael also compares the whale to a dragon, which includes St. George and his Dragon, and changes all settings and characters of the story to fit the sea and whaling—he then incorporates Hercules and is weary of this example due to Hercules being swallowed by the whale and never actually hunting it—by the end it’s turned around to make a connection to Jonah—a Hindu god is then considered a whaleman, being incarnated to respect his whaleman lifestyle-now Ishmael has this elite group in which he considers himself a part of.

top

Jonah Historically Regarded

As Ishmael expands on the Jonah story from the Bible, he informs us that Nantucketers don’t exactly believe every detail of the story—the holes in this story were pointed out by a man named Sag-Harbor (his hometown became his name)—but Ishmael doesn’t trust this story because the illustration showed a whale that had two spouts instead of one—only right whales have two—Jonah would have also been eaten by the gastric acid of the whale’s stomach—Ishmael comes in with his wisdom and suggests a story of Jonah’s whale being dead or not an actual whale at all—the geographical route of the whale in relation to where Jonah was swallowed to where he was released was longer than the three day journey suggested—Ishmael considers that they travelled around the Cape of Good Hope—Ishmael finally gives up on trying to counter the arguments made by Sag-Harbor and condemns him.

top

Pitchpoling

Ishmael contemplates the act of greasing the bottom of the whale boats and can’t understand how it actually makes the boat move faster across the water—Queequeg oils the bottom of his whale boat after the chase with the Jungfrau, and Ishmael believes it to be a waste of time—they spot whales and set their boats out in pursuit—they encounter trouble harpooning the whale, so they turn to an alternative method of taking down the whale—pitchpoling—take a pine spear or lance long in length and pretty thin—Stubb is given the glory of taking out a whale by pitchpoling—he mounts and cast the spear into the whale, hits in the first throw—the whale bleeds, and the crew strikes the whale until it dies.

top

The Fountain

Low and behold, Ishmael wants to explore yet another mystery— “The Fountain” or the spout— whether whales spout air or water is the question he’s looking into—of course, whales have to breach the surface in order to get air in their lungs, because they do not have gills—they breathe through this spout or opening located on the top of their heads—like a camel that preserves water, the whales can intake a large amount of air and stay submerged for awhile before surfacing again—the internal structure is a complex system of capillaries and veins within the whale, this carries the oxygen through the whale’s body—due to this, the whale will take in the same amount of air for each surfacing period and stay submerged for a fixed time—when a whale is spotted and driven underwater before it gets the right amount of oxygen, then it will have to continually surface since it didn’t get enough air before sounding—a whale is a vulnerable creature since its anatomy forces them to surface—now what is that spout for exactly? Ishmael is getting there…finally—it could be a way to discharge the excess water that was consumed when eating food—or is this spout just for breathing? —some whalemen have the idea that the spout of a whale spews a sort of caustic acid—Ishmael comes up with a hypothesis that this spout discharges that of a mist-like substance…which is just a mixture of water and air, clever Ishmael.

top

The Tail

And now Ishmael will obsess over the tail—where does this tail start on the body of the whale? —Ishmael comes to the conclusion that at the point where the circumference of the end of the tail could match the size of a man’s waist is the beginning—in what ways do they maneuver their tails? Let’s explore…moving forward, fighting humans, “sweeping” to get a sense of other foreign objects in the ocean, “lobtailing” playfully smacking the flat side of his tail on the water, and “peaking flukes” where the whale almost entirely exposes its body above the surface before sounding—did he just describe the trunk of an elephant while speaking of the whale’s tail? Ishmael believes he did, but, of course, he knows the whale’s tail is more distinguished—the tail becomes inexpressible for Ishmael and finally comes to realize that he just may not be the expert on the whale’s anatomy.

top

The Grand Armada

As the Pequod journeys across the sea, they come upon Asia, and the possibility of pirates—Ahab is adamant on a set route to Japan, not to stop but to pass through all of the crucial whaling grounds—Ahab believes they have everything they need—as the journey progresses, they spot a group of whales—once whales were a loner species but whale hunting has caused them to seek safety in numbers—uh oh, a ship is tracking them—Ahab delusions of the white whale or Moby Dick become more apparent, and it’s now a chase for him, crew unaware—they lose the pirates and finally get within a reasonable distance of the whales and lower the boats but they speed away again—hours spent chasing on the whaling boats—the whales then begin acting in a peculiar way—they depart to chase a specific whale instead of being the team they originally set out with—when Queequeg strikes a whale, it heads straight for the middle of the pack, putting them in danger—they are trying to maneuver their way out of this situation and end up using “druggs” to get the whales away from the boat—when one of the druggs is thrown, it gets caught and a hole is made in Ishmael’s boat—the harpoon comes loose and their boat comes to a sudden hault, leaving them stranded in the middle of whales in a panic—meanwhile, the younger whales take an interest in the boat—Queequeg and Starbuck begin interacting with the whales, a nonviolent encounter—a calm scene that exposes these creatures in a softer light, from mothers and their babies to newly birthed whales who are still attached to their mother—and Ishmael, of course, connects a philosophical meaning by coming up with a metaphor—all the while, some of the other boats are still having issues—they strike the tail of one, and in its pain it begins to thrash around and ends up catapulting the harpoon into another whale—the whales begin to enclose in an even tighter circle, leaving Ishmael in the middle, fighting out of the center—the whales flee and take off in a hurry, too fast for the boats, who are worn out anyway—they end up with two whales and a calmer sea, the rest are off and on their way.

top

Schools and Schoolmasters

Ishmael spends this chapter defining more whaling terms—“schools” are groups of whales—two types of schools: 1) “those composed almost entirely of females,” and 2) “those mustering none but young, vigorous males, or bulls” —typically, the school of whales chased by the whalemen will be composed of one male whale, the “schoolmaster,” and a bunch of females called the “harem”—“the contrast between this Ottoman and his concubines is striking; because, while he is always of the largest leviathanic proportions, the ladies, even at full growth, are not more than one third of the bulk of an average-sized male”—this is why whalemen often only hunt the harem and calves; the “Grand Turk” is “too lavish in [his] strength” and he “keeps a wary eye on his interesting family”—in the schools comprised of the “forty-barrel-bulls,” as the male whales age, they leave the school to “separately go about in quest of settlements, that is, harems”—Ismael’s final distinction between male and female whales is this: while male whales, if one of them is harpooned amidst a school, quickly abandon their comrade in need, members of a harem will linger around a harpooned whale so long to as become at risk of being harpooned themselves.

top

Fast Fish and Loose Fish

Ishmael devotes this chapter to explaining further some terms and occurrences mentioned in Chapter 87—a Fast-Fish is a whale that is connected to a boat or has any kind of waif (or other recognizable symbol of possession)—a Loose-Fish is a whale that is not fast—Ishmael explains that there are very few laws that define and regulate the matter of whale possession—juts two, actually: 1.) a Fast-Fish belongs to whomever it is fast to, 2.) a Loose-Fish is fair game—Ishmael goes on to discuss a few individual cases to show how difficult maintaining these simple rules can sometimes be—he resolves that “often possession is the whole of the law”—with a customary turn to metaphor, Ishmael enumerates many things in life that can be called “Fast-Fish” and “Loose-Fish”—“What are the Rights of Man and the Liberties of the World but Loose-Fish […] What are you, reader, but a Loose-Fish and a Fast-Fish, too?”

top

Heads or Tails

Ishmael ponders over the fishing laws of England—any fish captured on the English coast belongs to England, and to the King is appointed the fish’s head and to the Queen is appointed its tail—Ishmael gives a case of a fish being taken from some fishermen—he goes on to muse over William Prynne’s writing, “ye tail is ye Queen’s, that ye wardrobe may be supplied with ye whale-bone”—Ishmael points out that the bone used in ladies’ bodices is a particular bone in the whale’s head and not it’s tail—while he doesn’t doubt that the Queen of England is a mermaid from the sea, Ishmael does wonder if the head and the tail have an allegorical meaning—he doesn’t argue against the strange laws but instead insists that “there seems a reason in all things, even in law.”

top

The Pequod Meets the Rose-Bud

Days after the Pequod collects their last whale, they come across a foul stench—eventually, the identify the source of the smell: a French ship called the Bouton de Rose with whom they have a gam—it is obvious at once that the stench is coming from three whales tied to the Rose-Bud’s side—one of these is a “blasted whale” (a whale that died at sea) and another appears to have died from indigestion—the French report back to Ahab that they haven’t seen the White Whale—Stubb notes that the blasted whale will have nothing to offer the ship in profit until it occurs to him that the whale’s belly may contain ambergris—sly Stubb wonders if the French know about the ambergris—he boards the Rose-Bud and is able to convince the French that both whales pose a threat to the crew’s health—the crew of the Rose-Bud, especially the mate (who is doing some liberal “translating between Stubb and the French-speaking Captain), is happy when Stubb offers to tow the second whale away for them—as soon as the Rose-Bud is out of sight, the Pequod ties the whale up—Stubb expertly locates the ambergris in it’s belly.

top

Ambergris

Ishmael spends some time explaining what ambergris is and what it is used for—ambergris is a “soft, waxy” substance, which is “highly fragrant and spicy” and is therefore often used in “perfumery, in pastilles, precious candles, hair-powders, and pomatum”—Ishmael helps to define it’s worth by stating that the Turks carry it to Mecca “for the same purpose that frankincense is carried to St. Peter’s in Rome”—he ponders why whales are known mostly for smelling bad, since, in his estimation, whales are not particularly malodorous, dead or alive—In fact, according to Ishmael, “the motion of a Sperm Whale’s flukes above water dispenses a perfume, as when a musk-scented lady rustles her dress in a warm parlor”—Ishmael concludes by comparing the smell of sperm whale to the bejeweled elephant “redolent with myrrh” that was marched out of an Indian town to do honor to Alexander the Great.

top

The Castaway

A few days after the gam with the Bouton de Rose, “a most significant event befell the most insignificant of the Pequod’s crew”: Pip—first, a brief explanation of a ship-keeper: a person that stays on the ship while other crew-members pursue whales in the boats—anyone aboard skinnier, clumsier, or more fearful than average is sure to be appointed ship-keeper—long description of Pip’s character follows, full of pathos and fraught references to race—“over tender-hearted,” he was “at bottom very bright”—“Pip loved life.”—Ishmael notes the odd discrepancy between Pip’s fondness for “peaceable security” and the wild business of whaling—“back to the story…” (thanks, Ishmael)—a member of Stubb’s whaleboat (the after-oarsman) sprains his wrist, and Pip takes his place—he’s really nervous upon lowering for the first time but does alright, not encountering any whales—upon lowering a second time, they do encounter a whale, and when the animal raps the underside of the boat Pip leaps into the sea, “paddle in hand”—the whale makes a run for it, Pip gets tangled up in the line, and he is pinned to the side of the boat—all fired up with the hunt, Tashtego has to cut the line—“the whale was lost and Pip was saved”—in a rage, Stubb warns Pip never to jump from the boat again; if he does, Stubb won’t bother to save him—when Pip jumps from the boat for a second time, true to his promise, Stubb leaves him—within three minutes Pip is at least a mile from the nearest floating thing—Ishmael rhapsodizes on the “intense concentration of self” that occurs “in the middle of such a heartless immensity”—“my God! who can tell it?”—even when sailors go into the sea to bathe, they stay close to the ship—Ishmael explains that Stubb might have expected Pip to be picked up by the other whaleboats, but they had gone another way, chasing flukes—Pip is at last picked up (“[b]y the merest chance”) by the Pequod, which is in pursuit of the boats—although saved, Pip is changed—from that day forward he goes about the ship “an idiot; such, at least, they said he was”—“the sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul”—Ishmael suggests Pip saw God—ends the chapter by exporting the reader to “blame not Stubb too hardly”—foreshadows that a similar fate befalls him (!)—#orphan.

top

A Squeeze of the Hand

Stubb’s whale (“so dearly purchased”) is brought to the side of the Pequod for cutting, hoisting, and baling of the case—crew-members haul away the tubs of sperm as they’re filled—Ishmael launches into a detailed and hilarious description of the “sweet and unctuous duty” of squeezing the congealed lumps of sperm that form after it’s sat for a time in the tubs and cooled—the job is to turn the solidified masses back to liquid form—Ishmael extols the sperm’s cosmetic virtues—after only a few minutes of squeezing, “my fingers felt like eels, and began, as it were, to serpentine and spiralize”—squeezing the lumps of sperm is a welcome break from the hard work at the windlass—“as I snuffed up that uncontaminated aroma,—literally and truly, like the smell of spring violets; I declare to you, that for that for the time I lived as in a musky meadow; I forgot all about our horrible oath […] I felt divinely free from all ill-will, or petulance, or malice”—Ishmael squeezes the sperm until a “strange sort of insanity” comes over him—he starts unconsciously squeezing his coworkers’ hands, bringing on “an abounding, affectionate, friendly, loving feeling”—the world would be at peace, Ishmael suggests, if we could all squeeze sperm together: “Oh! my dear fellow beings, why should we longer cherish any social acerbities, or know the slightest ill humor or envy! Come; let us squeeze hands all around; nay, let us squeeze ourselves into each other; let us squeeze ourselves universally into the very milk and sperm of kindness!”—wishes he could squeeze sperm forever—he confesses to having “visions in the night” of “long rows of angels in paradise, each with his hands in a jar of spermaceti”—Breaks off to describe some other labors involved in preparing the whale for the try-works—the white-horse (tough pieces of whale meat, “obtained from the tapering part of the fish, and also from the thicker portions of his flukes”) has to be cut into portable blocks before going to the mincer—Ishmael describes some odd substances uniquely encountered in the whale fishery—1) plum-pudding: pieces of whale flesh that stick to the blanket pieces—“a most refreshing, convivial, beautiful object to behold”—Ishmael confesses to sneaking behind the foremast once to eat some—compares the taste to eating human flesh (!)—like the thigh meat of “Louis le Gros,” if cut away on the first day after venison season—2) slobgollian, which Ishmael “[feels] it puzzling adequately to describe,” is an “oozy, stringy affair” found in the tubs after prolonged squeezing—Ishmael hypothesizes that this substances is the membranes of the case coalescing—3) glurry: a “dark, glutinous substance” that is scraped off the backs of right whales and is therefore often found coating the decks of whaleships that hunt “that ignoble Leviathan”—4) nippers: “a short firm strip of tendinous stuff cut from the tapering part of the Leviathan’s tail”—whalemen sometimes use this piece of meat as a squeegee to clean the deck with—we descend into the blubber-room, where the blanket-pieces go to be hacked into pieces for boiling in the try-works—typically, two men work in here: the pike-and-gaff-man and the spade-man; the former holds the blanket pieces with a big hook while the latter stands on the blanket pieces to chop it up with a large, chisel-like implement—these men work barefoot, Ishmael says, which is dangerous business—“Toes are scarce among veteran blubber-room men.”

top

The Cassock

Chapter starts off with a vague description of “a very strange, enigmatical object” lying lengthwise along the lee scuppers during the “post-mortemization” of the whale—the most “surprising” of the whale’s parts: “longer than a Kentuckian is tall, nigh a foot in diameter at the base, and jet-black as Yojo”—the mincer comes along to carry it away; he needs the help of two other men to manage this “grandissimus, as the mariners call it”—it’s the whale’s penis y’all!—the mincer lays it out and begins to peel off its “dark pelt,” like peeling the skin off a boa—then he turns the pelt inside out, as you would a pant leg, and gives it a good stretching so its diameter is approximately doubled—he hangs it in the rigging to dry—after it’s dry, he takes the penis skin down, cuts off the “pointed extremity” (which, it turns out, forms a neck-hole), then cuts two slits in its sides for armholes—the mincer then slips himself bodily into the penis skin, which has now been transformed into a whaleman’s raincoat—“the mincer now stands before you invested in the full canonicals of his calling”—it’s the mincer’s job to take the tough blocks of white-horse, or “horse-pieces,” and cut them into thin slices of blubber called “bible leaves”— Ishmael is making a provocative and somewhat irreverent analogy between a Christian cleric standing before his congregation (donned in a cassock) and the mincer working away in his whale-penis-raincoat: “Arrayed in decent black; occupying a conspicuous pulpit; intent on bible-leaves; what a candidate for an archbishoprick, what a lad for a Pope were this mincer!”

top

The Try-Works