Several traditional Native American stories endure to this day concerning the origins of the island of Nantucket. While there are many significant differences in these accounts, they all have in common the legendary giant of Wampanoag lore, Maushop, who was thought to have resided in the area of Cape Cod. In one legend, Maushop, having grown weary of trying fall asleep with sand in his moccasins, kicked off one moccasin, which landed in the sea and became Martha’s Vineyard; still unsettled and growing frustrated, he kicked off his other moccasin, still farther, and this became the island of Nantucket. The island’s native populations attributed the clouds of fog that settle in the area to the smoke from Maushop’s pipe. In Chapter 14 of Moby-Dick, Herman Melville relates yet another legend concerning Maushop and Nantucket:

Thus goes the legend. In olden times an eagle swooped down upon the New England coast, and carried off an infant Indian in his talons. With loud lament the parents saw their child borne out of sight over the wide waters. They resolved to follow in the same direction. Setting out in their canoes, after a perilous passage they discovered the island, and there they found an empty ivory casket,—the poor little Indian’s skeleton.

In the Wampanoag tradition it is not one but several children that were thus carried off by a giant bird from the area known today as Cape C od, and it is not a party of Native Americans but the giant Maushop who, persuaded by the grieving mothers of the kidnapped infants, wades out into the ocean where he sees an unfamiliar island looming out of the mist. Here he discovers a heap of bleached bones beneath a tree, presumably the remnants of the repast of the feasting giant bird. Maushop then rested from his labors with a long, contemplative pipe that blanketed the island in a cloud of thick, grey-blue smoke.

od, and it is not a party of Native Americans but the giant Maushop who, persuaded by the grieving mothers of the kidnapped infants, wades out into the ocean where he sees an unfamiliar island looming out of the mist. Here he discovers a heap of bleached bones beneath a tree, presumably the remnants of the repast of the feasting giant bird. Maushop then rested from his labors with a long, contemplative pipe that blanketed the island in a cloud of thick, grey-blue smoke.

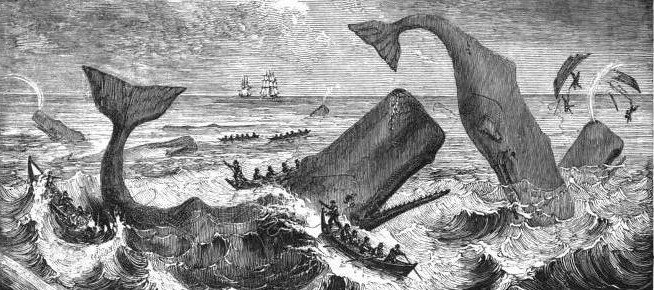

The fact that Melville doesn’t mention Maushop (also spelled Moshup, Maushup, among others) by name in Moby-Dick might point to nothing more or less than his ignorance of the rich history of Wampanoag legends pertaining to Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket. His interest in the version of the legend included in the chapter on “Nantucket” seems to be the sepulchral overtones of the island’s Native American pre-history. Perhaps Maushop should have attracted Melville’s attention more. After all, popular representations of the legendary giant often depict him fishing for whales with his bare hands in order to have them served at tribal feasts, as he is pictured in the tribal seal of the Wampanoag reservation at Aquinnah (or Gay Head, from where Tashtego hails). Maushop would seem to be a unique specimen of those early proto-typical whalemen in whom Ishmael the sub-sub is so often interested. In fact, Maushop might be considered his own whaleman and masthead in one and the same person.

“The Giant Moshup Catches a Whale,” mural by Stanley Murphy; Photo credit: Shelley Rotner, 2010.