8

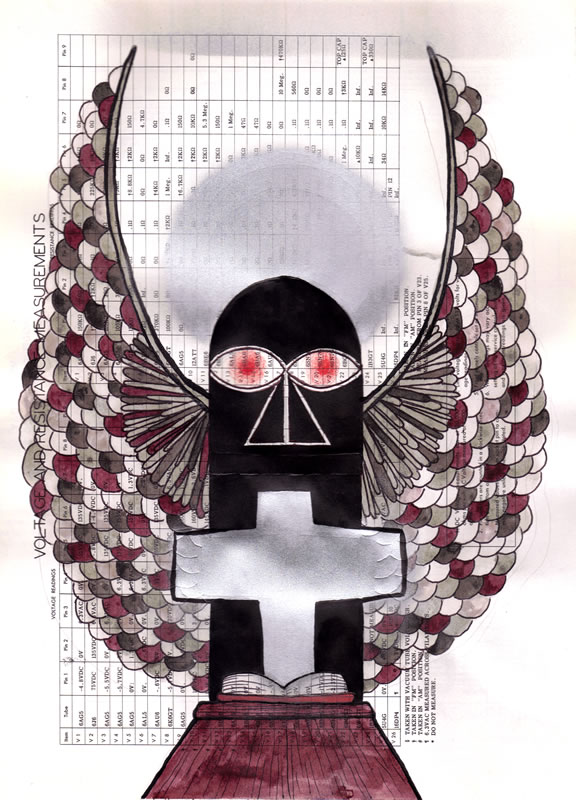

The peglike buoy figure of the water gazers in 2 returns in MK’s rendering of the “black Angel of Doom” Ishmael witnesses “beating a book” before a congregation in the “negro church” whose service he rudely interrupts then cruelly mocks before eventually finding his proper place at the Spouter Inn in New Bedford. The water gazers in 2 appear sexless and featureless apart from their beaky noses, hazy grey eyes, and multi-colored, -patterned wrappings. This canvas suggests that the figures are racialized, as this one is painted jet flat black from its smooth rounded head to the point where its tubular body vanishes behind a small brown pulpit uplifting a small book. The hazy, pointilated eyes are red, and a pair of large wings extend lifted from its sides, composed mostly of neatly layered small scallop shapes colored in various shades of maroon, grey, pink, black, and white (The wings have another texture where they meet the figure’s body: long slender U-shaped forms are colored in various shades of grey and black). A light, metallic grey spray-painted cross appears afront the black figure and a likewise painted nimbus crowns its head, framed between the uplifted wings.

The peglike figures seem to be MK’s answer to rendering the nameless landlubbers who populate the early pages of MD. This one is given prominence as the sole occupant of the canvas and by its great wings, but its most distinguishing and important feature is the one that differentiates it from the water gazers in 2: its blackness. Ishmael’s attitude (mock-revolted, dismissive) toward the congregation and pastor at the Black church is far from generous – indeed it’s dehumanizing – and MK chooses his moment on this cringeworthy page of MD to wrest some compromise between what Ishmael reports seeing and what he sees Ishmael seeing. Such compromises are fraught under the weight of US history. I’m anxious to witness how and where he chooses to grapple with illustrating Ishmael’s (and Melville’s) often racist characterizations of Black persons especially as the book goes on, having only begun myself with this “Angel of Doom” to sense the burden of (ir)responsibility that follows hard upon returning them into words. What is “doing justice” to a book like this, when it’s an injustice to some?

On the very edges of broad horizontal arms of the cross, where they extend past the tubular black body, you can make out traces of the scalloped lines composing the Angel’s wings beneath: a clue to the order in which the elements were created to compose this canvas – a detail I love.

MOBY-DICK, Page 008

Title: …and beyond, a black Angel of Doom was beating a book in a pulpit.

(7.75 inches by 11 inches; ballpoint pen, colored pencil, ink and spray paint on found paper; August 13, 2009)