12

8:14pm

I’ve sometimes drank as if to race death to the bottom of a glass, but I’ve also witnessed people drinking themselves as if literally to death. I’ll never forget the young man I saw running shirtless, full sprint, bent-waisted and headlong into the wooden railing of the porch of the mountain house where we were partying – repeatedly, ramming his head into the railing – nearly knocking himself out with every sickening crunch of the very top of his head against the well-fastened, not widely spaced balustrade, until he keeled over vomiting in the liriope and rhododendron. His friends said he was just drunk and always like that. We took him to the ER after seeing some worrisome evidence in his vomit, and he ended up having his stomach pumped. I laid off substances for some days, life went on, I graduated college, and I’m still no teetotaler. I’m drinking right now…

And what about how the gerund “drinking” can mean specifically drinking alcohol and be regarded as a straight-faced stand-in for drinking no other substance or elixir? “Whatcha doing?” I’m drinking. By that I surely cannot mean I am drinking milk, orange juice, tea, or water. Of course, I may be drinking any of those drinks and say “I’m drinking.” when asked what I’m doing, but even if it went like this – “Whatcha doing?” “Drinking.” “This early??” “Drinking coffee.” “Oh right [lol, eyeroll]” – it would be a bad joke, cheap sarcasm. One says “I’m drinking.” as if it could possibly mean, when asked “Whatcha doing?” and I say “Eating.” that I could only mean myself to be eating one type of food, or idly joking about not eating that one type of food. I’m drinking…

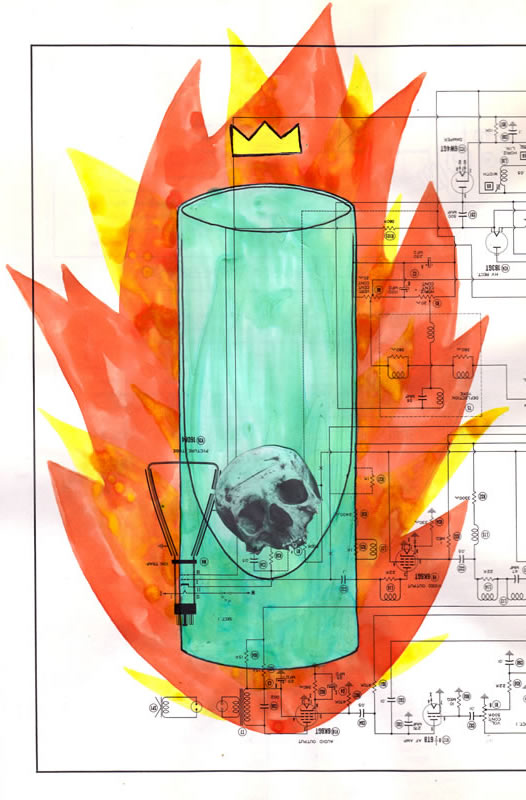

Drinking… For some it’s an easy compromise, for others an uneasy one, and for some it’s a disease. Whatever ease you have or lack or perpetually undo when it comes to drinking you’re reminded looking at this canvas that death is at the bottom of it. Language itself propels us toward a death’s head at the bottom of an empty, heavy bottomed glass, where was the fiery brew we would pour down the hatch as if to put out the deadly flame down below, or just behind.

9/3/21, 6:02am

The temperance movement biases Ishmael’s description of the bar at the Spouter Inn to no small degree. The barman, “another cursed Jonah,” sells sailors “delirium and death” from his jawbone den and at cheating prices. In contrast to the motley store of flasks, bottles, and decanters that house the “poison,” his customers drink from glasses that are “true cylinders” where they meet the hand and “tapered” where they hold their measures. MK honors this feature of the barman Jonah’s deceptive drinkware with his illustration of an empty glass – painted lightly in a “villainous” shade of green, set center-canvas against a backdrop of flowering flames, orange overlaid yellow. A jawless skull rests atilt in the narrowed false-bottom of the glass, not drawn but collaged into the canvas, adding a glaring realism to the otherwise simple illustration.

A basic, small tri-pointed crown, colored yellow, floats above the rim of the glass aligned with the sunken death’s head below, the only detail of the illustration that lacks an obvious analogue in the text of MD. Ishmael never ventures closer to the robber Jonah’s den than to note that you could park a carriage in there (cramped as the rest of the place is made out to be), so he never opines what royal distinction may apotheosize from a drained, abominable tumbler.

MOBY-DICK, Page 012

Title: Abominable are the tumblers into which he pours his poison.

(7.25 inches by 11 inches; acrylic paint, collage and ink on found paper; August 17, 2009)